Your Ultimate Guide to ACL Rehab

Introduction to Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries

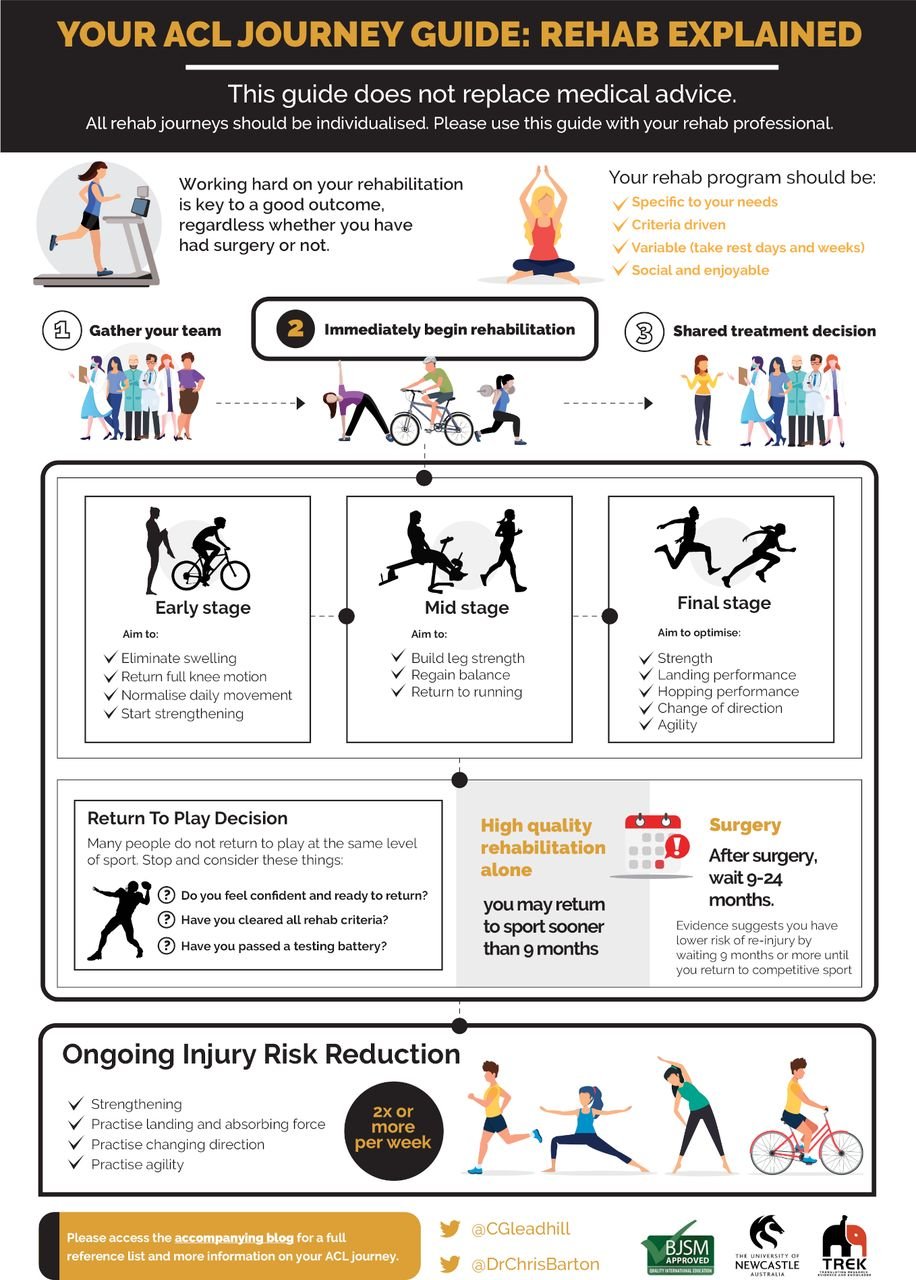

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is a crucial stabilizing structure in the knee, which often falls prey to sports-related injuries. If you or someone you know has recently or previously experienced an ACL injury, or are on the road to recovery, it is important to know that rehabilitation is a significant part of this journey. This blog post will guide you through the complexities of ACL rehabilitation, providing expert advice, helpful insights, as well as tips and exercises that can aid in your recovery. In this blog we explore the rehabilitation journey following surgical management, the Cross Bracing Protocol and conservative management. Regardless of your treatment choice, restoring your knee's function, your confidence in movement and getting you back to your sport and the activities you love is our ultimate goal at Back to Bounce Sports Physiotherapy.

The Back to Bounce Way:

At Back to Bounce, our Mission is to help athletes of all levels, abilities and ages to achieve their maximum performance and full potential. We aim to give each athlete the individualised support they need based on their injury, their goals and lifestyle to achieve their goals. Our approach is to aim for all of our clients to achieve their highest potential through rehabilitation based on;

An individualised approach

Progressing rehabilitation based on regular assessments

Working closely with the client, coach, family members, orthopaedic specialist and/or sports doctor and GP for a comprehensive, collaborative journey where the individual is supported throughout

Focusing on long term strategies of motor pattern learning, skills and confidence building

With this in mind, let’s look at the stages of ACL rehabilitation and what you can expect when you attend Back to Bounce Sports Physiotherapy for your rehabilitation.

Firstly, what causes an ACL rupture?

How did I rupture my ACL?

There are a few different ways an ACL rupture can occur.

Excess Valgus of the Knee ie knees pointing inward

Excess External femoral rotation ie thigh twisting outwards and lower leg twisting inward ( to demonstrate stand feet shoulder width apart and twist your trunk to look over one shoulder, you will feel the twisting force on the foot your twisting away from)

Poor muscular strength/control (Koga et al., 2016)

Understanding the causes and risk factors of ACL injuries

Causes: ACL injuries are typically caused by a combination of mechanical and biological factors, often occurring during high-intensity sports and movements. Here are some common mechanisms:

Non-contact Mechanisms:

Sudden deceleration or change in direction: The ACL is most commonly injured during quick deceleration or when athletes change direction suddenly (e.g., cutting, pivoting).

Landing from a jump: Landing from a jump, especially with improper technique (e.g., landing with the knee straight or inward), can put excessive stress on the ACL.

Knee hyperextension: Hyperextension, or when the knee bends backward too far, can place strain on the ACL and result in injury.

Rotational movements: Rotating the body while the foot is planted can cause excessive torque (twisting force) on the knee joint, leading to ACL injury.

2. Contact Mechanisms:

Direct blow or collision: Although less common, ACL injuries can occur from direct contact or a blow to the knee, often in contact sports like football or soccer.

Tackling or blocking: In contact sports, players might be injured when an opponent's body or the ground impacts their knee at an awkward angle, often resulting in a hyperextension or rotational injury.

Risk Factors: Female athletes are two to eight times more likely to sustain an ACL compared to their make counterparts, especially in sports like soccer, basketball, and volleyball. This difference is attributed to a combination of anatomical, hormonal, and biomechanical factors. Women typically have wider pelvises, which leads to a greater Q-angle (the angle between the hip and knee). A larger Q-angle can lead to greater stress on the ACL. The prevalence of ACL injuries is becoming more and more common. An increase in female participation in sports such as AFL, rugby league and union, hokey, basketball and soccer has also led to an increase in prevalence in ACL ruptures.

Anatomical Factors

Ligamentous laxity: Some individuals have inherently more flexible ligaments, which can make the ACL more prone to injury due to the decreased stability in the knee joint.

Pelvic width and Q-angle: A wider pelvis increases the Q-angle and places greater stress on the ACL during dynamic movements.

Femoral notch size: A smaller femoral notch (the groove where the ACL sits) can increase the risk of ACL injury, as there is less space for the ligament to move safely during knee flexion.

Knee alignment and structure: Poor knee alignment (such as valgus or "knock knees") can place extra strain on the ACL during sports activities.

Extrinsic (External) Risk Factors

Sport Type:

High-risk sports: Sports involving cutting, pivoting, and jumping are considered high-risk for ACL injury. These include soccer, basketball, volleyball, football, and skiing. The high demand for quick direction changes, landing from jumps, and rapid deceleration increases the stress on the ACL.

Contact sports: Sports like football or rugby involve frequent collisions, which can increase the likelihood of ACL injuries from direct hits or awkward positions during tackles.

Environmental Conditions:

Playing surface: The type of playing surface (e.g., artificial turf vs. grass) can influence injury risk. Research suggests that playing on artificial turf may increase the risk of ACL injuries due to reduced traction, which can lead to more forceful twisting or hyperextension of the knee.

Footwear: Improper or inadequate footwear, such as shoes with poor grip or excessive cushioning, can lead to instability during dynamic movements and increase ACL injury risk.

Weather conditions: Wet or slippery conditions may alter an athlete's ability to change direction quickly or land safely, which can increase injury risk.

I’ve ruptured my ACL, what do I do now? Diagnosis and treatment options for ACL injuries

The knee is a complex structure and there may be additional injuries alongside your ACL tear. You should always seek professional advice from a doctor or physiotherapist as soon as possible after an injury. If an ACL injury is suspected, you will be guided to have an Xray and MRI scan to investigate for other associated pathologies such as meniscus tears, fractures, bone bruising and other ligament injuries. Put simply, the options of ACL management are: Surgical treatment typically involves reconstructing the torn ACL with a graft (usually tissue taken from the patient) to restore the function of the ligament. ACL reconstruction is commonly performed for athletes, active individuals, or those who wish to return to sports that involve cutting, pivoting, or high-impact movements. Non conservative management invovles rehabilitation, physiotherapy and can involve bracing (such as the Cross-Bracing Protocol), and modifications to activity levels. This option is often chosen for individuals with lower activity demands, who don’t intend to play change of direction sport, or who prefer to avoid surgery.

Both surgical and conservative management of ACL injuries have their advantages and drawbacks, and the choice between the two largely depends on the individual’s activity level, the severity of the injury, and their personal goals. Although ACL injury is unfortunately frequent in many sports involving landing, pivoting and contact, the journey of rehabilitation is a very unique experience for every athlete. For athletes or individuals who require high knee stability, ACL reconstruction is often recommended. For individuals with lower activity demands or those with partial tears, non-surgical management may be a viable option, though it comes with the risk of ongoing knee instability and potential future complications. The best treatment plan should be developed in close consultation with individual’s healthcare professionals, considering all aspects of the patient's lifestyle, health, social support, and long-term goals.

Rehabilitation Following ACL Reconstruction Surgery

Before embarking on any journey, it’s crucial to have a clear understanding of the desired outcome, goals and the steps needed to achieve it. While many rehabilitation processes begin with a clear starting point and direction, they often lose focus along the way or fail to reach their goal, ultimately compromising the athlete’s recovery. For most athletes, the ultimate goal of rehabilitation is:

To return to their pre-injury sport.

To do so without experiencing symptoms (such as pain or instability) in the knee.

To minimize the risk of future injury to either knee.

To return to, or even exceed, their pre-injury level of performance.

The stages of ACL injury recovery and the importance of rehabilitation

Following ACL reconstruction surgery, there are various stages involved between the first days on crutches to finally returning to the field/court of your chosen sport. This blog outlines the various stages involved in the ACL rehabilitation journey from early, through to middle and finally end stage.

Prehab/Early Rehab

In the first few weeks after initial ACL injury, or reconstructive surgery, our goals are to reduce acute inflammatory process to allow bone bruising and swelling to settle and to restore normal knee function and range of motion. Here we aim to restore knee flexion and extension range, quadricep, hamstring and calf muscle activation, gait and function. Working on proprioception (the body's ability to sense its position in space) and neuromuscular control is essential from the outset. Simple exercises that involve standing balance or weight shifting can help promote better knee control and prevent future instability, whether you choose to have surgery or not. Research shows better outcomes by doing early rehab and is critical for setting the foundation for successful recovery. If weight bearing is indicated, depending on the individual’s MRI results, we work on regaining good walking technique to ensure the knee and surrounding structures heal optimally. Here is it important to monitor pain and swelling. Any exercise or movement that significantly increases pain or swelling should be avoided, and rehabilitation should be adjusted.

Mid stage- Building muscle

Building muscle mass with hypertrophy training whilst continuing to work on neuromuscular control. Predominantly strength and building cardiovascular fitness. Aims of restoring injured leg to within 95% of the opposite side in terms of strength. Here we start to add more complex lower limb exercises such as step ups, lunges, Bulgarian split squats, proprioceptive drills and more complex balance exercises. Here it is essential to incorporate the kinetic chain into exercises to ensure good core and trunk control is maintained with all exercises. Now we progress balance drills and work on increasing confidence and proprioception. We are gradually preparing for higher-impact movements by slowly introducing dynamic movements and sports-specific drills, starting with controlled low-impact activities.

Third Stage- Building Power, Return to Straight Line Running

Power based jumping and landing practice and improving the ability to produce power and absorb force. Working on landing technique, proprioception, reaction time and return to straight line running once you pass key objective criteria. Often the “12-week” mark post-surgery is suggested as a common time to begin a return to running program. However, return to running is not only about how much time has passed since your surgery but is based upon meeting objective criteria and clinical tests. Other criteria include minimal to absent pain, restoration of full knee extension range of motion, 95% limb symmetry of knee flexion range of motion, absent knee effusion/swelling, hop test performance, and quadriceps and hamstrings strength testing. Importantly, using a time-based criterion fails to account for individualised tissue healing responses, pain, strength, and the surrounding muscles’ ability to control the rapid and high loads to the knee that are involved in running.9

Fourth stage- return to sport training

Perhaps the most critical in all stages is the final return to sport specific training phase.

Return to sport activities and training. Training drills, game simulation and then tests that have to be passed in order to return to sport. Here we work on restoring movement quality, increasing physical condition, restoring sport-specific skills and increasing chronic training load. This phase encompasses linear movement, multidirectional movement patterns, jump landing practice, technical skills and practice simulation. Then, the athlete will progressively return to team training and gradually return to competitive match play. This process allows the player to focus on regaining sport-specific movement with physical, technical, and tactical performance while developing psychological readiness to perform.

Testing Parameters Throughout the Journey

Pain free range of motion- we want to ensure full extension (straightening) and flexion (bending) of the knee.

Strength- quadricep, hip, hamstring and calf greater than or equal to 95% of the uninjured side. Single leg training is essential to building strength. Double leg exercises such as squats and deadlifts are great exercises, but to specifically strengthen the affected leg, single leg exercises are a must.

Jump testing- double leg and single leg vertical jump and reactive jumping, triple hop for distance. At Back to Bounce, we have the latest technology that provides accurate measurement of performance measures after ACL reconstruction. Using the VALD force deck platforms often used in elite sport, these measures provide valuable insight into how your recovery is tracking for a safe return to sport. This data provides information about muscle strength, power, kinetic chain loading, plyometric acceleration and deceleration to make an informed decision about what to focus on in rehab. We use testing as guideposts to steer the direction of the rehabilitation and what components need to be worked on specifically.

Agility testing- change of direction testing and field-based testing

Make it stand out

W

Why is Psychological testing so important?

After an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injury, psychological readiness is a crucial aspect to assess before an athlete returns to sport. Psychological readiness tools help ensure that athletes are mentally prepared for the physical demands and potential emotional challenges of returning to competition. Evidence suggests up to 24% of people can re-injure their knee after returning to their sport following an ACL injury, however this risk is significantly reduced in people who pass important psychological return to sport criteria. Research by Arden and colleagues emphasize that psychological readiness is a key determinant for the decision to return to sport following an ACL injury. They argue that athletes who experience fear of re-injury, low confidence, and high levels of kinesiophobia (fear of movement) are less likely to return to sport at the same level as before the injury.

Several tools and questionnaires have been developed to evaluate psychological readiness after ACL rehabilitation, such as:

The Return to Play Index (RTPI)

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Return to Sport After Injury (ACL-RSI) Scale

The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK)

The Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (PRRS) Scale

The Return to Sport-Confidence Scale (RTS-CS)

The Sports Injury Psychosocial Readiness Scale (SIPRS)

It is a fact of ACL rehabilitation that hard work is involved during each phase in order to optimise outcomes, both physically and mentally. People with better functional performance have lower chance of re-injury and better long-term outcomes, including lower rates of osteoarthritis. Psychological readiness screening is an essential part of the return-to-sport process after ACL injury. Tools as discussed allow healthcare providers, coaches, and sports psychologists to assess the mental and emotional factors that can influence an athlete’s return. While physical recovery is critical, addressing psychological concerns such as fear of re-injury, confidence, and emotional readiness ensures a more successful and safe return to sport. It’s essential for rehabilitation programs to integrate these tools and work with the athlete to address both physical and psychological aspects of recovery.

Why is return to sport testing so important?

Even if an individual follows the most perfect rehabilitation plan following an ACL reconstruction, there is still a risk of reinjury when returning to sport. A study showed that when returning to sport following an ACL reconstruction, people were at a 6 times higher risk of reinjury for up to two years following surgery. Of the athletes with reinjury, 20.5% of these occurred on the opposite leg, and only 9% on the previously injured leg.

That’s where passing return to sport criteria and tests is important to reduce the risk of reinjury, or a new injury, as much as possible. Returning to sport prior to passing these objective markers places the individual at a higher risk of reinjury. A study in 2016 found that athletes who did not meet six clinical return to sport tests before returning to their sport were 4 times more likely to have an ACL rupture.

This is why at Back to Bounce Sports Physiotherapy, we rigorously go through extensive testing with our patients before encouraging them to return to their sport. Ideally, we would like to never have patients return with another ACL injury in the future. Through consistent assessment using our VALD Force Deck technology to provide real time information on landing mechanics, feedback on asymmetries in landing mechanics as well as data on the quality of the landing on both limbs and strength comparing sides. This information helps us to guide our rehabilitation plan and also encourages the athlete to work on their landing strategy, maximising their motor learning. We educate patients on the important of continuing their rehabilitation program even after they return to sport with the aim to reduce their risk of recurrence as much as possible.

How to reduce the likelihood of injury

Exercise based injury reduction programs have been proved to reduce the incidence of ACL injuries. At Back to Bounce, we offer ACL Injury Prevention Programs, specifically aiming to reduce the risk of injury by practicing specific jump landing practice and strength exercises. It is important to include different components in your program such as strength, landing and force absorption, change of direction and agility, to name a few.

These programs are important to participate in to reduce the risk of ACL injury, whether you have had a previous ACL injury or not. There are a few key components of effective programs such as consistent lower limb and trunk strengthening, balance and neuromuscular challenges including practicing landing technique. Completing these programs is an important consideration coming in to the final return to sport stages of your ACL rehabilitation and remain a key component of your program when you do return to sport. There are many injury reduction programs to choose from, including the FIFA 11+ program, the Netball KNEE Program, the Prevent injury and Enhance Performance (PEP) Program, the ACTIVATE World Rugby program.

To learn more about ACL rehabilitation at Back to Bounce Sports Physiotherapy, head over to the following pages:

https://www.backtobounce.com.au/blog/cross-bracing-protocol-acl-rupture

https://www.backtobounce.com.au/blog/acl-injury-prevention

https://www.backtobounce.com.au/blog/acl-vald-force-decks

https://www.backtobounce.com.au/blog/acl-injuires

References:

Arundale AJH, Bizzini M, Giordano A et al. Exercise-based knee and anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and the American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018;48:A1-A42. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.0303.

Pinczewski LA, Lyman J, Salmon, LJ. A 10-year comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with hamstring tendon and patellar tendon autograft: A controlled, prospective trial. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(4):564-574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546506296042.

Grindem H, Risberg MA, Eitzen I. Two factors that may underpin outstanding outcomes after ACL rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 14 July 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095194.

Toole AR, Ithurburn MP, Rauh MJ et al. Young athletes cleared for sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: How many actually meet recommended return-to-sport criterion cutoffs? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47(11):825-833. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7227.

Patterson B, Culvenor A, Barton C et al. Poor functional performance 1 year after ACL reconstruction increases the risk of early osteoarthritis progression. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:546-553. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101503.

Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:804-808. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031.

Paterno, M. V., Rauh, M. J., Schmitt, L. C., Ford, K. R., & Hewett, T. E. (2014). Incidence of Second ACL Injuries 2 Years After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(7), 1567–1573.

Kyritsis, P., Bahr, R., Landreau, P., Miladi, R., & Witvrouw, E. (2016). Likelihood of ACL Graft rupture: Not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(15), 946-951.

Willy, R., 2023. THE LATEST GUIDANCE ON RETURN TO RUN AFTER ACL RECONSTRUCTION. Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal https://journal.aspetar.com/en/archive/volume-12-targeted-topic-rehabilitation-after-acl-injury/THE-LATEST-GUIDANCE-ON-RETURN-TO-RUN-AFTER-ACL-RECONSTRUCTION